How to Talk to Your Child About Gender and Sexuality

Caregivers play an active role in the formation of the attitudes and beliefs of children, including how they feel about themselves and others. Children look to the adults in their world for guidance and support, so caregivers should take the opportunity to discuss important aspects of life like gender and sexuality.

During Pride month and all year round, conversations like these open the doors for children to learn about respecting others and conversing about their own sexuality. How can parents and caregivers guide these interactions? What’s important to consider when talking to children about gender and sexuality? And why are these conversations so crucial to mental health, particularly the mental health of LGBTQIA+ youth? Let’s begin.

Understanding Gender, Sexuality and Other Terms

Understanding Gender, Sexuality and Other Terms

When a child asks a question on the topic of gender or sexuality, caregivers can serve children well by giving accurate answers. Guiding children begins with building our own knowledge base.

LGBTQIA+ is an acronym used to be inclusive and expressive of anyone who identifies within this community. The first three letters “LGB” refer to sexual orientation—lesbian, gay and bisexual. The “T” refers to gender identity or transgender. The “Q” stands for queer or questioning and the “I” for intersex. The “A” may stand for asexual, aromantic or agender.

What is Gender?

Gender is defined as a social construct of norms, behaviors, and roles that varies between societies and over time. An example of socially constructed attributes is the color “assignment” given to each gender: girls like pink, and boys like blue.

Gender interacts with, but is different from “sex,” which refers to a person’s biological status and is typically assigned at birth, usually on the basis of external anatomy. Sex is typically categorized as male, female or intersex.

Here are additional terms to understand:

- Cisgender: A person whose current gender identity corresponds with the sex assigned at birth.

- Gender Expression: How someone expresses their gender, including how they present themselves to the world through the clothing they wear, their hair or the way their speak. It’s all the ways we do and don’t conform to the socially defined behaviors of masculine or feminine.

- Gender Identity: This refers to one’s own internal sense of self as male, female, neither or both. It’s personal and may not align with the sex assigned at birth.

- Gender Non-conforming: People who don’t conform to traditional expectations of their gender.

- Transgender: A person whose sex assigned at birth differs from their gender identity.

What is Sexuality?

Sexuality is an umbrella term for an individual’s personal and diverse feelings, thoughts and behaviors toward other people. This includes how humans express a connection to others biologically, psychologically, physically, emotionally, socially and spiritually. Sexuality can also be broken down into more detailed terminology, including:

- Asexual: A person who is not sexually attracted to other people.

- Bisexual: A person who is attracted to more than one sex or gender.

- Gay: A sexual orientation that describes someone who is attracted to people of their own gender.

- Lesbian: A woman who is emotionally or sexually attracted to other women.

- Pansexual: A person who can be attracted to all different kinds of people, regardless of their biological sex or gender identity.

- Queer: Originally used as a pejorative slur, queer has become an umbrella term to describe the myriad of ways people reject binary categories of gender and sexual orientation to express who they are. People who identify as queer embrace identities and sexual orientations outside of mainstream heterosexual and gender norms. Although it is a reclaimed term within the LGBTQIA+ community, it is still considered offensive to many and should only be used if necessary and appropriate.

- Questioning: People who are figuring out their sexual orientation or gender identity.

- Sexual Orientation: This term refers to a person’s physical, romantic, and/or emotional attraction to another person. For example: gay, straight, lesbian or bisexual

If some of the terms above seem unfamiliar or different than those used in the past to describe similar ideas, remember that language changes. Some people may use terms to describe themselves that are less common today, and others may describe themselves in a different way entirely. It’s okay! What matters most is respecting and recognizing people as the individuals they are.

Want to take a deeper dive into common terms surrounding gender and sexuality? PFLAG, the first and largest organization dedicated to supporting, educating, and advocating for LGBTQ+ people and their families, has a comprehensive glossary sharing a wide range of definitions.

Tips For Talking to Children About Gender and Sexuality

Begin Conversations Early

Some caregivers may worry that conversations about gender and sexuality will be too much for a younger child. Of course, the way these conversations are handled should remain age-appropriate. But starting the conversation early helps children understand that sexuality is important, questions are normal, and you are a safe and trustworthy person when big feelings or questions arise.

Create an Open and Safe Environment

Ensuring that children feel safe to have open discussions will allow for more chances to connect. They need to know that they will be loved and accepted no matter what. In addition to fostering a connection, children can understand that you’re willing to work through the nuances of sexuality and gender. And sharing information about these important topics could lead to higher acceptance, equality, and respect for diverse populations and healthier future relationships.

Listen and Find Teachable Moments

Teachable moments are everywhere: all around the community, in movies or on television, as a part of song lyrics or in books — everywhere. When a moment presents itself, an easy way to open a conversation is by asking, “What do you think about that?”

Then, take the time to listen and hear what the child is saying and thinking. They may already have a decent understanding of these topics, or perhaps they know some things but are confused about others. This is an opportunity for connection.

Take a Pause (If you need to)

Children are known for asking questions or discussing topics that seem out of the blue, but if a child is bringing something up, they have most likely noticed something or heard someone else discussing it.

If what your child brings up catches you off-guard or at a time when you feel unprepared to have the discussion, it’s okay to take a pause. Consider how you might respond. You may need to do some research to relay the right information. Or maybe you’re unsure how to discuss it in an age-appropriate way. What matters in these moments is keeping open communication. Let the child know that you want to continue the conversation later after you have had more time to think or find answers.

Be Honest

Children need and deserve honesty. This is key to building a shame-free, safe environment — and maintaining a trustworthy relationship.

Give Age-Appropriate Information

Guiding the conversation with age-appropriate information is vital. Not only will it help children understand based on their cognitive development, but it can help you provide information that isn’t too mature.

- Ages 3-5: Pre-school-aged children need simple, concrete answers. Try to stick with only answering the question at hand, and not giving extra details. For example, if a child asks why a friend has two mommies or two daddies, you could respond by letting the child know that all families are different and some have two mommies or daddies, some have a mommy and a daddy, and some may have a mommy or a daddy.

- Ages 6-10: School-aged children are beginning to develop their capacity to process more details and, consequently, also notice more about what’s happening in the world around them. As they explore and become curious, their questions may become more complex, and so should your conversation. At this age, children may notice outward appearances and differences in gender expression. For example, if a child has a question about why someone dresses differently than societal norms, you can say that dressing in a certain style doesn’t make someone a girl or a boy, and ask about that child’s personality or character traits.

- Ages 11-18: Once a child begins their pre-teen and teenage years, and goes through puberty themselves, the topics of conversation and understanding deepen. Sexual orientation in themselves becomes more apparent, and some or most of their peers will be open about themselves. It’s a time of exploration and processing. As this happens, they may ask questions out of curiosity or navigate how someone (especially caregivers) might react. Remember to keep judgments at bay. Lead by asking how your child thinks and feels about the topic, and listen earnestly to what they have to say.

Why It’s Important to Talk About Gender and Sexuality with Kids

Children and teens go through so many changes. Beyond their physiological changes, they’re learning about who they are, what they believe and how they fit into the world. For adolescents with varying gender identities and sexual orientations, life can present unique challenges.

Talking about gender and sexuality with kids allows them to feel seen, heard and supported. It’s reported that at least 60% of LGBTQIA+ youth struggle with anxiety, depression and thoughts of suicide. It’s also proven that family and community acceptance and support reduce the risk of suicide in LGBTQIA+ children.

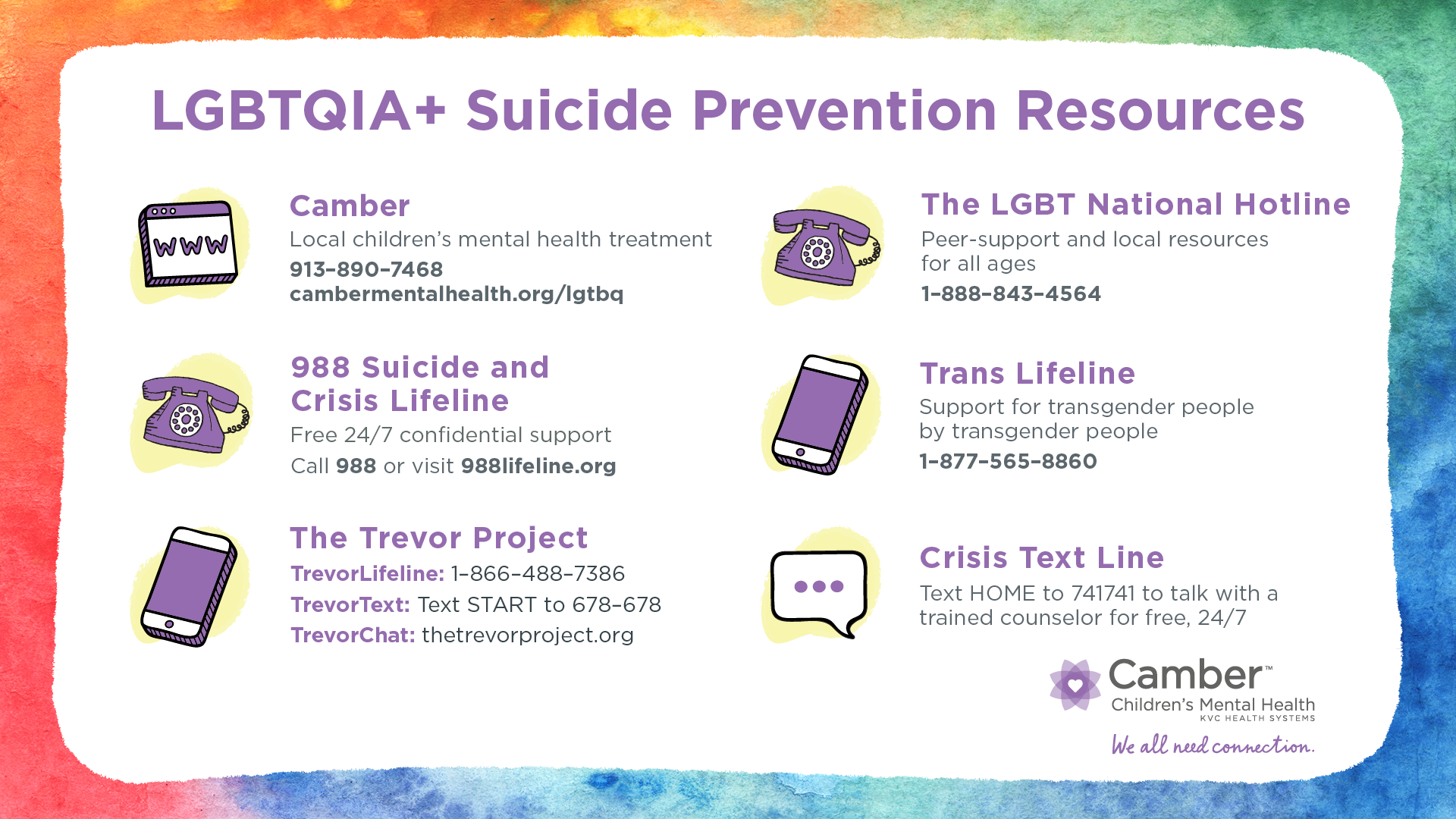

Issues surrounding gender and sexuality can also be directly connected to mental health. If a child is struggling with their mental health or experiencing painful emotions, it’s important to seek professional support right away. Check out this guide for more information about how you can support people in the LGBTQIA+ community, the warning signs of emotional distress, and suicide prevention resources.